- publish

A verification email has been sent.

Thank you for registering.

An email containing a verification link has been sent to .

Please check your inbox.

An account with your email already exists.

A framework to assess COVID-19 investment risks and opportunities

- Fri 03 April 2020

Having a disciplined process to decide when – and what – to buy is vital.

Although some argue we are living through an almost unprecedented threat to civilisation, history suggests panic is often worse than the pandemic.

For investors it is vital to understand that new fortunes can be established during these rare and often brief periods when information finds itself in a vacuum. It is perhaps less obvious that while the circumstances might be different with each crisis, the human response in investment markets is surprisingly similar.

Here I will attempt to offer a framework for conservative long-term investors that may help calm fears and simultaneously provide a platform for a potentially superior financial outcome through a framework.

Nobody forecast it would be a virus that popped the bubble in asset markets, but they didn’t need to. One of the outcomes of the framework I will offer is an ability to recognise a bubble.

Montgomery Investment Management spent a great deal of time last year warning in the press and on our blog that asset markets were stretched, were very late in their cycle and seriously disengaged from reality.

Having raised cash ahead of the tech wreck of 2000 and the GFC in 2008/09, it was again obvious in 2018 and 2019 that markets had disengaged from any rational assessment of the true worth of a company’s future earnings.

Several signs made it obvious that markets were dangerously expensive and vulnerable to any unexpected event. Indeed, our domestic funds raised significant levels of cash ahead of the market’s sell-off. The path forward, now we are firmly in a crisis, is equally obvious. More on that after outlining the basic framework.

Speculating is not investing

First, it is vital to recognise the difference between speculating and investing. Investing involves treating shares as pieces of businesses. Speculating is betting on the ups and downs of share prices. Betting on up or down is akin to betting on black or red at a casino.

By approaching investing as acquiring an ownership stake in a business there are significant changes to one’s outlook. The short-term gyrations of prices matter less and you can focus on the long-term accumulation of wealth that occurs when businesses generate profits, retain those profits, and then generate high rates of return on the growing pool of capital. This process takes years, rather than days or weeks, so an investor can put the market’s gyrations in context.

Second, you have heard that time in the market is more important than timing the market. But this statement needs some refinement. Time is the friend of a high-quality business and the enemy of a poor business. The longer you remain invested in a poor business, the worse the outcome will be.

Therefore it is incumbent on you, or the fund manager you employ, to be able to identify high-quality businesses, ensuing your time in the market is a rewarding one.

Defining quality

Three characteristics define a high-quality business.

The first is superior profitability as demonstrated by a high rate of return on shareholders’ equity. What is a high rate? Double digits is a good starting point but when it comes to returns on equity, May West was right when she observed, “Too much of a good thing … is wonderful.”

Of course, sustaining a high rate of return on equity is challenging because no sooner have others recognised a superior return, they will enter the market in competition, lowering prices and eroding the returns once available.

Only businesses with a valuable competitive advantage – an unreplicable point of difference – can sustain high returns in the face of competitive attacks. In business, high returns attract competition and a competitive advantage protects a business from would-be competitors.

Another important consideration is debt. We want businesses whose returns on equity are not artificially boosted by lots of gearing. The current crisis will press the economic brakes for such an extended period that pressure will be placed on weaker businesses to raise fresh capital or debt in order to survive. However, the information vacuum accompanying the pandemic will diminish the appetite for providing credit. Already highly geared companies will face bankruptcy.

Finally, we want a business that generates lots of cash. If businesses receive cash at the same time they make a sale, that is helpful. If they can receive the cash for a sale of an item before they have to pay for the goods (think Woolworths and Coles receiving immediate payment for goods sold but paying suppliers on 90 or 120-day terms) even better.

It is also essential that the company’s cash flow after investing in itself is sufficient to do attractive things, like making rationally priced and synergy-generating acquisitions, buying back shares or paying dividends.

Ultimately, we want a business that can take large amounts of equity and generate very high cash returns on it, without the need for debt.

Valuation is key

Once you have identified a high-quality company it is important to avoid overpaying for it. From personal experience, this requires patience. For a fund manager like me, with a firm view of what value looks like, it has been a genuine challenge resisting client demands to invest in the latest and greatest business ideas of 2017, 2018 and 2019.

Fund managers who invested in high-flying tech stocks were the heroes of the boom, with share prices doubling, tripling and quadrupling. Today, many of those companies, once priced on potential rather than proof, have fallen by 70 or 80 per cent.

To avoid overpaying, an investor must understand intrinsic value. That concept requires its own chapter, which I included in my book, Value.able. You can find out more about how to value a company there.

Identify a quality business at the right price and you do not have to worry about predicting its share price, because that will follow business performance over the long run. And once you train your eye on the long run, you will worry less about short-term share price declines, instead seeing them as long-term opportunities.

Investing and COVID-19

That brings us to the current crisis, which I believe is the fourth in a series of seven or eight such events I expect to see in my lifetime – if I live to 90.

Back in April 2018, in my column for The Weekend Australian, I wrote” “When it comes to equities, be certain of this: there are market darlings today whose share prices will decline 50, 60, 70 and even 90 per cent in the next 12 to 24 months.”

Unfortunately, while we hope investors heeded those warnings, we did look very out of step with the roaring prices at the time.

To be fair, the conundrum for investors last year was that cash had been so painfully poor at generating a return that is acceptable, many felt forced to take on more risk. To our minds, however, investors had not really appreciated the extent of the risks they were adopting.

Eschewing the one per cent returns on cash balances, investors migrated to equities for their superior yields and hoped-for capital gains. What was forgotten in the mad dash for a better return was that 1 percent is better than minus 20.

Many investors have now swallowed that bitter pill. We note, in particular, the very companies we warned investors to avoid – those with stratospheric share price gains – are those through which investors have suffered most.

Here is a list of signs the market was on an unsustainable course:

Markets were expensive

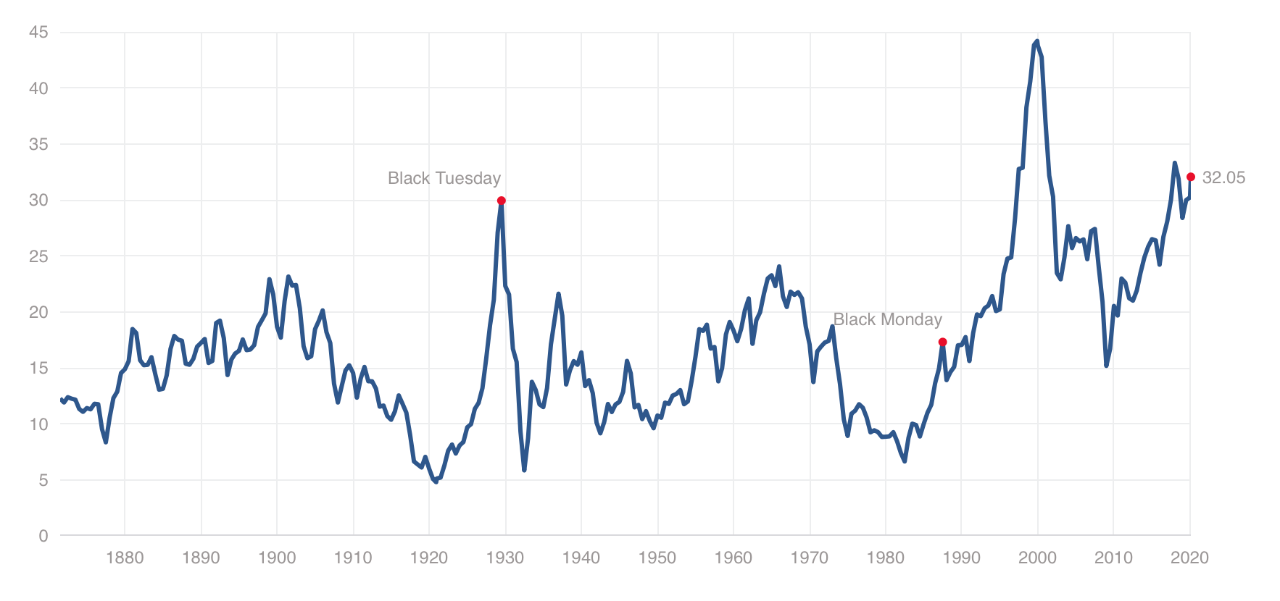

To begin with the US market had been extremely expensive for some time. As figure 1 demonstrates, the US S&P 500 was trading on a cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE) of more than 32 times in January.

To put this in perspective, an investor could look all the way back to 1870 and find only one instance when the market was even more expensive, and that was during the tech bubble of 1999/2000. The coronavirus pandemic struck at the time of the second-most overvalued US stock market ever.

Figure 1. S&P 500 CAPE RATIO 1870 – 2020

Source: Montgomery Investment Management

In Australia, the story was similar. The S&P/ASX 200 Industrials Index, excluding financials, was trading on a record earnings multiple of almost 27 times. Of itself that may not have been a problem, remembering that interest rates had declined precipitously. The issue was that consensus earnings estimates were in decline. It was also relevant.

For more than two years, earnings multiples had been rising and in January 2020 Australian stocks were trading on an earnings multiple of about 26 times.

Meanwhile, and since June 2019, one-year forward earnings per share estimates for the ASX 300 had been declining. In the absence of a resurgence in economic growth, the combination of rising prices and falling earnings has rarely ended well. In 2019 and early 2020 investors were paying more for poorer-quality companies and failed to appreciate that their fear of missing out caused them to adopt more risk.

There were of course other issues such as a bubble in private equity markets and the US Treasury yield curve inverted more than 70 per cent in August amid a major repo liquidity crisis. But investors only needed to know that prices had disengaged from intrinsic values to realise a higher weighting to cash was warranted.

A framework for navigating corrections

Invariably, different triggers and nuances accompany each crisis and market dislocation, but each is ultimately accompanied by an information vacuum that produces a correction.

Importantly, every correction is also fed by a fear that no solution will emerge, that capitalism or even humanity is at risk. Truthfully, there are equities that benefited from a misallocation of capital during the preceding boom, when the potential was valued more highly than the proof.

For investors in many of those companies, there will be a permanent loss of capital. But it is worth remembering that corrections tend to conclude before a solution is broadly declared, and solutions have always been found. Those focused on quality and value find that opportunities are therefore greatest when what is temporary is treated as permanent. This too will pass.

In today’s crisis we observe that a government can stimulate their way out when citizens are worried merely about the economy. When investors or consumers are worried about their health, however, no financial incentive can encourage people to spend and take risk with their wellbeing. Queues of people awaiting social security payments will rekindle memories of depressions and instil even more fear, but these too are common to recessions.

Today it is the market’s realisation that concerns about health can have more serious and potentially lasting consequences for the economy, that have exacerbated the market’s declines.

This correction is therefore different to the GFC, different to the tech wreck of 2000 and different to the corporate debt-inspired crash of 1987. But in many respects, it is the same – it is a crash.

Importantly, several at the Montgomery office have invested through those periods and know the long-term reality is not as frightening as the short-term panic inspires. Humans, it should be remembered, are adaptable and resilient.

Important reminders

Remember, cash is most valuable when nobody else has any.

In reality, there will not be a total shutdown of the world. China and many Asian economies are operating, re-scaling their operations and economies again. While liberal Western democracies are only just entering a period of rapid virus detection rates and fatalities, and while markets are surprised, remember this too will pass.

China may already be showing that steps can be taken to contain the virus and stop its spread. Soon, I expect countries currently experiencing parabolic growth rates of infection will slow the growth and then the panic will abate.

All COVID-19 eyes on the United States

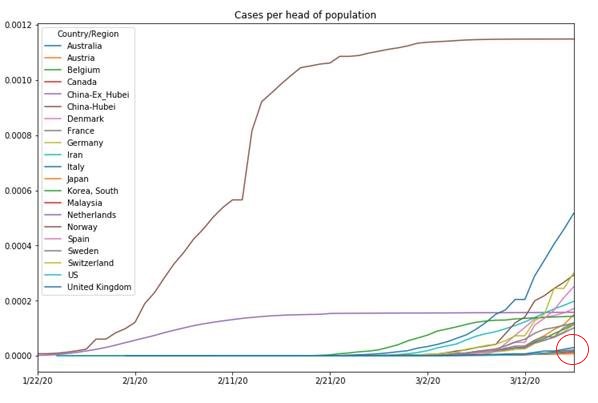

Our most shocking discovery in the very early days of February was that despite the US having a population of 330 to 340 million, they were only conducting an average of 40 tests a day, on average, through January. In February that increased to an average of 92 a day.

Our thesis was a pretty simple one. The US would eventually ramp up its testing and when it did, would be shocked by the detection rates – the number of people confirmed as positive – and also the fatality rates.

The market was blissfully unaware of this in early February. At the time of writing, the US is witness to 18 per cent detection rates and the market now fears the rate is going to rise materially in coming weeks.

As figure 2 demonstrates, at 20 March 2020, the United States’s handling of COVID-19 can only be described as an abject failure.

Figure 2. United States; Growing fast from a low base and a very late start

Source: Montgomery Investment Management, The Montgomery Fund

The possibility of further shocks remains but much of the worst in terms of COVID-19 scenarios has been reflected in recent price declines.

Opportunities

What are the possible opportunities? What is the path forward from here? Firstly, let us think about a framework for a crash. Stage one is probably almost complete and that is accompanied by an unwinding of the growth premium that was built into prices prior to the correction commencing and reflected in those tech stocks.

Also accompanying stage one is the market being shocked by the extent of the infection. We think there is some of that to go in the US, but we are pretty close to completing stage one. Markets are currently in an information vacuum and when investors do not know how serious the situation could become, asset prices overreact.

Holding cash when everyone else wants cash but does not have any is when opportunities can be taken advantage of. Comments about the world ending or this being Armageddon or a great depression, feeds into that vacuum and pushes prices down even further.

Stage two sees a little more rationality appear but at the same time companies start raising money and pulling their guidance. In Australia, toilet rolls may start reappearing on supermarket shelves and remain there. The hoarding slows and the financial market panic eases along with the volatility.

Once the market realises humanity will survive, a more rational assessment of the impact on the economy starts to occur. Obviously, we are going to see revenues cut deeply. We know that even many of the high-quality companies we like they are basically going to torch their earnings and revenue for the next 12 months.

Assume revenues of zero. Modelling businesses and their revenues and costs will remain difficult for many months but we are less concerned about next year’s revenue and earnings because our investing time horizon is much longer than that.

We are going to be targeting those companies that have sufficiently strong balance sheets, can endure a year or 18 months of zero revenue, and do not need to recapitalise (raise funds).

We might even look at companies that do need to recapitalise, but only after they have done so, probably at deeply discounted prices.

As an aside, one of the observations we can make is that market bottoms often coincide with a round of companies engaging in deeply discounted rights issues. We have already seen Webjet, Flight Centre and Ooh Media approach the market for capital. The longer and deeper the economic slowdown, the more we are going to see capital raisings and bailouts.

Stage three could be steep and deep or relatively benign. The magnitude of the third stage depends on the extent of the recession and the degree to which credit supply for corporates is impacted. In times of crisis, liquidity is everything.

There will come a point in the not-too-distant future, where the World Health Organisation announces that the coronavirus danger is over. There is also the real possibility of a vaccine. When those things happen there is going to be a lot of pent-up demand for travel.

In conclusion, this crisis will pass like all others before it. My sincere best wishes for the next year or two. Navigating it well will set up your portfolio and wealth for the next decade.

About the author

Roger Montgomery, Montgomery Investment Management

Roger Montgomery is the Chief Investment Officer of Montgomery Investment Management and the author of Value.able – How to identify the best stocks and buy them for less than their worth, available here.

ASX acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia. We pay our respects to Elders past and present.

Artwork by: Lee Anne Hall, My Country, My People