- publish

A verification email has been sent.

Thank you for registering.

An email containing a verification link has been sent to .

Please check your inbox.

An account with your email already exists.

Outlook for Australian shares in 2021

- Fri 04 December 2020

Three key factors to consider when choosing companies next year.

It’s December 2019, and you’re tasked with providing an outlook for Australian shares for the next 12 months.

Somehow, you manage to predict with perfect foresight the events of 2020: bushfires, a global pandemic that would claim more than 1.2 million lives, a total ban in Australia on international travel, state borders to slam shut, the second-most populous city in the country to enforce a lockdown for 112 days. You see 1 million Australians unemployed as the country enters its first recession in 29 years.

As the year draws to a close, you predict the president of the United States will refuse to concede the 2020 election outcome.

Given this outlook, what prediction are you likely to make for Australian equities?

With perfect foresight, you’d have been more likely to stick your money under the mattress than in the market – I think few people would’ve guessed that the market would be pretty much flat over the 12 months from December 2019.

This thought-experiment highlights the core issue with forecasting: it’s hard to predict the big events that move sharemarkets, and it’s even harder to predict how markets will react to them.

So rather than vague prognostications on what next year might hold, when assessing the top three things that matter for investing in 2021, we assess the same three things that always matter for any investment, at any time.

1. Balance sheets

Corporate debt levels hadn’t seemed to matter to the market much over the last few years, and some companies had been lured by cheap debt to fund share buybacks or increase dividend pay-outs.

The economic impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis quickly changed the market view on the importance of financial strength, with over $30 billion of equity capital raised on the ASX in 2020 to repair balance sheets.

(Editor’s note: Almost $56 billion was raised in secondary capital on ASX in the calendar-year to October 2020, including emergency capital raisings).

However, it’s not just during global crises that financial strength matters. Over the long term, companies able to fund their operations, including growth, from internally generated cashflows tend to outperform those that repeatedly need to come to the market to raise equity.

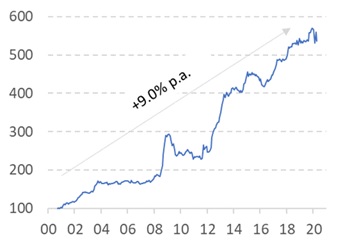

This collection of companies that repeatedly require new equity capital, or “equitisers”, has underperformed by 9% per annum relative to low equitisers on the ASX over the past 20 years, according to Airlie analysis.

Figure 1: Long Term Outperformance of Companies with Low Levels of “Equitisation”

Source: MST Marquee, Airlie Funds Management

Balance sheets matter, and we would avoid those companies that are highly geared heading into 2021.

We would note that balance sheets look conservative across the board, in part reflecting a year of substantial capital raisings, with average net debt to underlying earnings (EBITDA) currently at 1.8 times, which is 20% below the average of the last 10 years of 2.2 times, according to our internal research.

This could set the stage for a more rewarding year for capital management for investors than 2020, with resumption of dividends, buybacks and potentially mergers and acquisitions (M&A) as companies utilise balance-sheet capacity.

Balance sheets matter, and we would avoid those companies that are highly geared heading into 2021.

We would note that balance sheets look conservative across the board, in part reflecting a year of substantial capital raisings, with average net debt to underlying earnings (EBITDA) currently at 1.8 times, which is 20% below the average of the last 10 years of 2.2 times, according to our internal research.

This could set the stage for a more rewarding year for capital management for investors than 2020, with resumption of dividends, buybacks and potentially mergers and acquisitions (M&A) as companies utilise balance-sheet capacity.

2. Management

It has been said we only get to judge the quality of management decisions made during the good times after the cycle turns and the “tide goes out”. We certainly had the tide go out in 2020.

Whether it was the need to write down acquisitions purchased at the top of the business cycle, repair balance sheets with dilutive equity capital raisings and dividend cuts, or jettison assets that are now “non-core”, the recent market dislocations have shone the spotlight on management decisions made over the past cycle.

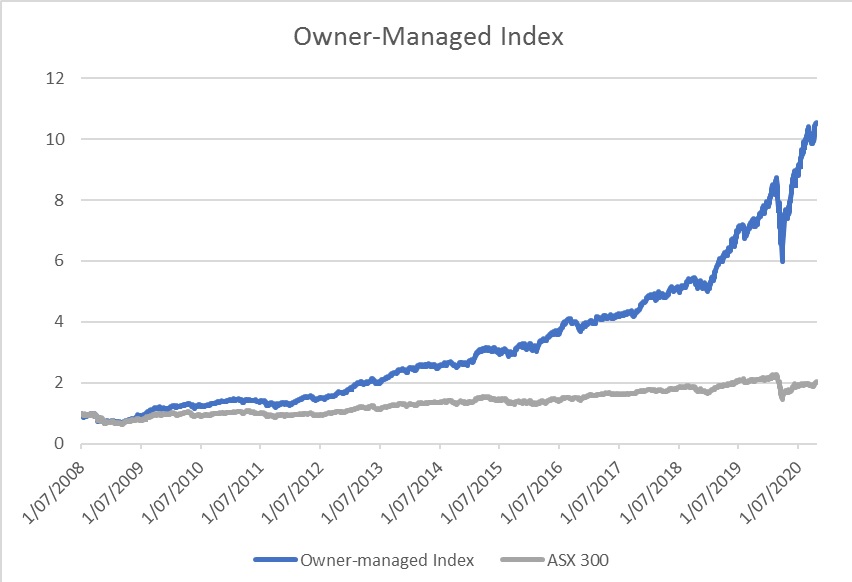

Looking ahead, we back managers who have “skin in the game” (significant equity holdings in the business) and think like owners. Owner-managed businesses, which are run by original founders who retain significant ownership stakes, are the ultimate model of this.

As the chart below shows, investing in the owner-led businesses listed on the S&P/ASX 300 index over the past 12 years would’ve returned 10 times your initial investment, versus an index return of two times, according to Airlie analysis.

We expect that tilting your investments towards companies with high insider ownership (founders, key executives owning stakes in companies) will continue to be a good strategy.

Figure 2: Index of owner-managed businesses has significantly outperformed the market

Source: Factset, Airlie Funds Management

3. Valuation

The enticement to invest right now is clear: low interest rates, with governments and central banks globally willing to act as a safety net for demand.

In Australia, the Reserve Bank has lowered the price of money to an all-time low, and has signalled it will keep this cash rate for at least the next three years. (The market, on balance, expects further falls as shown by the ASX RBA Rate Tracker). Historically, when you lower the price of money, people want more of it.

The government is underwriting jobs via payments such as JobSeeker and JobKeeper, and encouraging a pull forward of investment via capex allowances. We expect these measures to flow through to business investment, Australian house prices and consumer sentiment.

Coupled with stronger corporate balance sheets and relative valuation appeal, versus dwindling savings rates, it’s easy to construct a positive outlook for the Australian economy/equities in 2021.

However, the big risk is also interest rates. As economies recover, if we saw a meaningful uptick in inflation, we would expect markets to react negatively (and sharply).

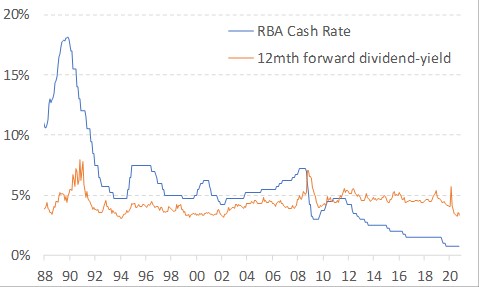

The key question when considering valuations is whether you’re being adequately compensated for taking risk. The Australian market looks expensive versus history at a headline level, trading at 25 times forward Price to Earnings (PE) multiple, versus a 10-year average of 17 times, which would suggest you aren’t.

However, when you consider the dividend yield of the market (3.3%) versus the cash rate (0.1%), the picture looks less clear – you’ve never been paid more for putting your money in the sharemarket versus a bank deposit. This analysis presupposes the businesses you invest in pay dividends.

Many loss-making companies (particularly in the tech sector) don’t pay dividends and have enjoyed significant re-rates this year. We would be wary about these valuations, where risk/reward looks negatively skewed.

Figure 3: The ASX 200 is expensive on a PE multiple but yields are attractive compared to term deposit rates

Source: MST Marquee, Airlie Funds Management

Summary

We see 2021 as a year to be selective. Valuations and uncertainty are elevated. We prefer companies with solid balance sheets, run by managers with skin in the game, and would avoid loss-making businesses in “hot” sectors that have enjoyed a substantial re-rate in 2020 on a “lower for longer” interest-rate thematic.

Hopefully in 2021 we enjoy some precedented times, for once.

Related links

READ MORE

View featured articles from ASX publications On the Board and Listed@ASX.

About the author

Emma Fisher, Airlie Funds Management

Emma Fisher has over 10 years’ investment experience with roles in portfolio management and investment research at Airlie Funds Management, Fidelity International and Nomura Securities. She holds a Bachelor of Commerce (Liberal Studies) from the University of Sydney.

Airlie Funds Management (Airlie) is a specialist Australian equities fund manager that brings together some of Australia’s most experienced industry participants. Airlie has an active, value-based investment style that aims to deliver attractive long-term capital growth and regular income to its investors.

Founded by John Sevior and David Cooper in 2012 and headquartered in Sydney, Airlie manages approximately $7.33 billion of funds under management at 29 May 2020 across a range of Australian equities strategies, primarily for institutional and high-net-wealth clients. Airlie is a wholly owned subsidiary of Magellan Asset Management Limited.

The Airlie Australian Shares Fund (Managed Fund) (ASX:AASF) is available on ASX.